On trees

Talking to Timur earlier this week I mentioned how nice it was being back in Delhi for the most fleeting of breaks. In particular, I said, it was wonderful to be back in a city that has become really, wonderfully green. A lot of the trees that I saw being planted in the middle of the then barren road dividers when I was in school have now grown up, providing at times a complete canopy of green cover. I live very near the Lodi Gardens, which is a huge privilege and just so wonderful because the area can be so pleasant at times that you can just about forget about the chaos of the city.

I mentioned the trees in particular because seeing that kind of greenery was such a relief and such a break from Istanbul. There are few trees here. In general, what really characterises the lay of the land in this city is its construction. There is so much of it. Because Istanbul is built on hills and spans two continents it affords vistas that other cities might not. What you see are just endless houses. Absolutely endless. Every time I have stop and say, “Wow, there are a lot of people here.” It gets exhausting at times, the endless sea of construction. In the last few months the addition of the heat tired me even more. Hence all the running away to the Aegean.

One of the most frustrating things about being in Istanbul these days is seeing what is happening to the city. There is even more construction going on, the city is expanding even more. Earlier this month, I was working on a short report on the real estate sector in Turkey, Istanbul in particular. It was an exercise in self-induced depression. So much of Turkey’s growth is tied to the construction sector and so much vested interest lies in construction that I fear this city will be destroyed because of it. Some of the new infrastructure projects being undertaken by this government seem so blatantly engineered to aid land speculation and spur construction in as yet sparsely populated areas of the city that I am at times shocked by the sheer shamelessness of those pushing these schemes.

A third bridge is going to be built on the Bosphorous. Because Istanbul has a major traffic problem and to aid the transport of goods that are unloaded at the Black Sea, we are told. This bridge is being built so far up north the Bosphorous that it does not actually connect any of the main inhabited neighbourhoods in Istanbul. What it does do is make land that is forested land easily accessible and more valuable. As for the bit about transport of cargo and goods — apparently that was an excuse used for the second bridge too, but more than 90% of traffic on both bridges is non-commercial. A third airport has also been announced. Also up north towards the Black Sea. And then there is also the Prime Minister’s crazy project, a man-made canal from the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara running parallel to the Bosphorous. What all these projects do is use up the city’s much needed and incredibly scarce forested land. It will have even fewer trees.

Timur pointed me to this post; the words of Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar and what he wrote about Istanbul’s trees in his Beş Şehir (Five Cities).

If there were another beauty in old Istanbul that rivaled the grandeur of architecture, it was the trees. But could this be called a rivalry? If the truth is wanted, trees are our architecture’s and our entire lives’ most generous helper. As much as they know how to complement white marble and chiseled stone, they also know how to agree with a ruined roof, a fountain, its decoration lost to neglect, its basin shattered. They resemble a poem recited in the name of the sun.

After our conversation I went back to my copy of the book and found the section where Tanpinar talks about Istanbul’s trees. At one place he writes that the loss of a tree is like the loss of a big architectural work of art. And yet what remedy is there, he asks, when we have, for centuries, even longer, become used to both.

Everything Is Ficition

Sepoy linked to this piece in the New Yorker and I found this paragraph particularly touching (and true) —

And I mean that—everything is fiction. When you tell yourself the story of your life, the story of your day, you edit and rewrite and weave a narrative out of a collection of random experiences and events. Your conversations are fiction. Your friends and loved ones—they are characters you have created. And your arguments with them are like meetings with an editor—please, they beseech you, you beseech them, rewrite me. You have a perception of the way things are, and you impose it on your memory, and in this way you think, in the same way that I think, that you are living something that is describable. When of course, what we actually live, what we actually experience—with our senses and our nerves—is a vast, absurd, beautiful, ridiculous chaos.

Langour

I haven’t been here in a while and the general listlessness I feel these days is partly responsible. Istanbul is hot now, not terribly hot like Delhi, but hot enough with it strong sun and terrible humidity. I usually walk the last leg of my journey to the office in the morning (this journey involves taking the ferry across the bosphorous, a funicular uphill and then either a short metro ride or a fifteen minute walk), but this week I bailed and decided I would take the metro instead. The prospect of air-conditioning won over the thought of arriving at work drenched in sweat and wanting yet another shower. Perhaps it is the heat that has also made me listless with Istanbul. This has never happened and I never thought it ever would, but I do feel like Istanbul and I are in the midst of a little tiff. I feel frustrated by the heat, the crowds, the ramazan drummers. Even looking at the beloved skyline frustrates; the multitude of skyscrapers that are being built going higher, becoming more concrete everyday.

Last month I went to the UK for a week and I think that only added to the confusion I feel. Till my work permit came through I was going back there so often it hardly felt as if I had left, but this time it was clear I had with no idea of when I will or can go back. I miss the place, I miss the people there, I even miss the stodgy full English. The grey wet miserable cold weather was welcome (till it was not, having outstayed that welcome). I feel at times like a loutish teenager who wants everything — I want to be here and there. And yet, I also have a long list of complaints and issues with both places and if I am not here I know I will wish I was. At any rate, I think all my frustrations with this city will son dissipate, it is too beloved for it not too. In the meantime, I am currently in the midst of a massive love affair with the Aegean and that takes away some of the angst of being annoyed with this place. This weekend I am going away to Ayvalik and Cunda and that has been an incredibly happy thought in this vile, vile heat. I am looking forward to the green of the olive trees, turquoise blue of the sea and the smell of fish.

On 1453

I wrote about the film Fetih 1453 and the conquest of Istanbul for al Majalla here. They edited out the bit about the Panorama Museum (I was completely over the word limit! At any rate, the museum is great.) So here is the whole piece.

This May 29th marked the 559th anniversary of the conquest of Istanbul. Thousands of people gathered in the soft drizzling rain on the Golden Horn in the evening to watch the celebrations. Some climbed trees to get a better view of the stage that had been set up on the water, others contributed to the atmosphere by wearing Ottoman costumes. Almost everyone was waving the national flag. To fill the gap before the spectacle actually began, the organisers played some kind of neo-Ottomanist militaristic tune on a loop. “This is infectious,” said my friend swaying to the music, along with the vigorously flag-waving crowd, “It reminds me of what Woody Allen said about not being able to listen to too much Wagner for fear of wanting to conquer Poland.” When the proceedings began a voiceover reminded the crowds of Sultan Mehmet’s statement before the conquest – “Either I will take Istanbul or Istanbul, me.” Heavy cheering ensued. This might not have been what the Sultan actually said, but almost everyone in the crowd would have been familiar with these words that had been emblazoned over the city on the posters of the summer mega blockbuster ‘Fetih 1453’.

When ‘Fetih 1453’ (Conquest 1453), a historical epic about the conquest of Istanbul, released in February – the premiere was a matinee show at 14.53 – it was the most expensive film to have been made in the history of Turkish cinema. The film boasts 16,000 extras, CGI effects, numerous sword fights and battle scenes, free use of violence and a cameo voice-over by the Prophet himself. The film’s ambitiousness meant an ever-expanding budget during filming and trouble with financing. By the time shooting had wrapped up the film had taken the best part of three years and an estimated $17 million to be made. Still, the producers need not have worried about the budget, which was massive by Turkish standards. On just the opening weekend, a staggering 1,405,000 viewers flocked to the movie theatres to watch the film. It was the best opening weekend any Turkish film had ever seen. Since then, Fetih has become the highest grossing Turkish film of all time, earning back about three times the cost of making the film.

The success of the film is, perhaps, not all that surprising given that its release has coincided with a period of particularly strong love for all things Ottoman in Turkey. Much has been made of the current government’s so-called ‘neo-Ottoman’ foreign policy, but interest in Turkey’s Ottoman past has very much become a feature of cultural life in the country, with ‘Ottomania’ affecting realms from food to fashion. Soon after the film’s release school children were taken on school outings to see the film. A restaurant in the heart of Istanbul’s touristic Sultanahmet district that specialises in Ottoman food brought out a special ‘Conquest Menu’. More recently, when the football club Galatasaray won the Süper Lig trophy the Turkish daily Radikal used the Fetih poster to report and celebrate the club’s victory. The club’s manager Fatih Terim, whose name literally means ‘conqueror’, was shown as the conqueror of Istanbul.

Swords and Sandals; Violence and Hedonism

But what of the film itself? I went to see the film expecting a historical piece that follows the journey of Sultan Mehmet II and his successful siege of Constantinople. What I ended up seeing was a story about the conquest that gets mostly co-opted by a love triangle between the heroic Ulubatlı Hasan (a character of dubious historical reality, but one who is nevertheless celebrated in Turkish folklore as planting the conquering Ottoman flag on the Byzantine palace and getting shot down by arrows in the process), the Genoese commander of the Byzantine forces, and a cross–dressing female canon member of the Ottoman army who makes the victory possible. As a way of assurance that the film was not completely insane, my Turkish friend guaranteed that all school children did learn the Ulubatli Hasan version of the conquest (though there was no love triangle mentioned). “In school when we had to draw the conquest, I remember drawing Ulubatli Hasan planting the Ottoman flag, with tons of arrows in him.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, for all the money spent on the film, it has come in for criticism from critics and historians for its recreation of the past, and especially its depiction of the Byzantines, who are painted with broad brushstrokes as evil hedonists. A Byzantine historian friend fumed that the film was so off the mark that “it seemed the makers had not even bothered to read a basic history of the period”. The critic Emine Yıldırım was even harsher on the film writing “Obviously, the filmmakers did a lot of research and expended a lot of effort to depict the Ottoman state as genuinely as possible, but why has this not also been the case for the Byzantines? In the film, Emperor Constantine XI and his statesmen seem to have been transplanted from a comic book universe where there are no grey lines between good and evil.” The simple oppositional set up of the film not only ignores the fact that there were a large number of Greeks who were fighting on the Ottoman side, but also some of the continuity the Ottomans themselves saw between Byzantine and Ottoman rule. On his conquest of the city, Mehmet claimed the title ‘Caesar of Rome’.

Apart from problematic historical representation, a fault found in many a historical blockbuster, there is also the violence. The journalist Andrew Finkel says he saw the film as an unconscious celebration of war. At the end of the film, once Constantinople has been conquered Sultan Mehmet enters the Hagia Sofia, where a group of terrified Byzantines have been hiding, kisses a baby and declares that the citizens of the city have nothing to be afraid of and can practice their religion as they like. Though the event is historical fact, coming on the back of endless minutes of violent battle scenes, it seems too superficial a gesture. The film also makes a big play of Mehmet allowing the defeated army to bury the King Constantine’s body as per their rituals, though in actual fact the fate of the last Byzantine Emperor’s body or its burial place is highly disputed. It is this kind of token nod to tolerance that caused Yıldırım to declare the film a “muddled pool of hypocrisy” that not only engenders antagonism against the West, but also reinforces an aspiration for superiority. The columnist Burak Bekdil added to the sentiment writing, “Sadly, millions of Turks will go to the theatres to feel proud of their ancestors and to visually show their children “our greatness.” We are great not only because “we had the power of the sword” but, even more sadly, because we still adore the idea.”

The Conquest in Public Consciousness

These criticisms, however, were just a few in a sea of praise for the film, which even Prime Minister Erdoğan has said was “well done”. Andrew Finkel tells me that he thinks 1453 has a continued resonance because in many ways the story of the conquest has resonance not just for the political classes who want to re-enact that ultimate triumph again and again, but also for the many people who have come or want to come to Istanbul. Despite being banished to the side-lines by the new Republic in its first decades, Istanbul has been the throbbing heart of the country and a magnet for migration since the 1950s. Today the city is home to nearly 15 million people. According to the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality, the city has seen a migration of nearly 11 million people over the last fifty years. “You can say that Istanbul has been conquered multiple times even in my lifetime,” says Finkel. “The Istanbul of today is not the city it was in the ‘60s, ‘70s or even the ‘90s. The notion of conquering the city and making it one’s own has a strong resonance.”

A few weeks after the release of the film, I paid a visit to the Istanbul Panorama Museum. The museum is located near the city’s Byzantine Theodosian walls and recreates in three dimensions the moment of the conquest. In a country where museums are not exactly popular excursion venues, it took an approximately forty-five minute wait amongst a crowd of mostly religiously observant visitors to get in. The museum has been popular since its opening in 2009, but I also wondered if the release of the film had caused a spike in the number of visitors to the museum. Inside, the rush of crowds made it difficult to clearly see the panorama. At one point a whisper went around the room that Sultan Mehmet’s face could be seen in the clouds. After being convinced by my Turkish friend that she too could not see the Conqueror’s face, while everyone around us exclaimed their excitement at a spotting, we made the most of the distraction to focus on the panorama itself. What I saw of the panorama was well worth the effort – the paintings were beautiful. The museum’s location means that the created panorama maps out on to the walls outside tying in the epic story of the conquest with material culture that witnessed it and still survives. As I walked along the city walls afterwards I could not help but be struck by how deserted they were. Though the walls have undergone restoration since 2005, large segments seem abandoned and desolate. The visitors had come and seen the museum, but paid little or no attention to the actual place where the historical event had taken place. It was perhaps easier to think of the fantastic, movie images when thinking of the conquest than trying to reimagine the glorious moment looking at the ancient walls.

In spite of the early Republic’s rejection of all things Ottoman, the conquest of Istanbul has one of the two main central dates in Turkish historiography. After the 1980 coup, the military government embarked on a wide-ranging cultural project of Turkish-Islamic synthesis. In the run up to the coup the country had been racked by violent divisions between the left and right-wing political groups and it was hoped that Islam and Turkish nationalism in combination would prove to be an all-inclusive ideology. It was a final consolidation of the re-embrace of religion that had first become visible in Turkish politics and public culture in the 1950s. After the Welfare Party (the predecessor of the currently-ruling AK Party) won the 1994 Istanbul municipality elections, there was a determined effort to reinstate 1453 as the defining event in the life of the nation. In the Istanbul neighbourhood of Üsküdar, two red sculptures of the dates 1453 and 1923 overlook the Bosphorous. One is the year the city was conquered, the other the year the Republic was established. It might be too simplistic to say that 1453 is now more important, but the release of Fetih has certainly contributed to a certain swagger and nationalistic pride over the conquest and made it even more central to popular culture and politics in Turkey today.

A town on the border

My overwhelming sense of the place when I was in Kars was that it was just a very strange town. My first acquaintance with the place was through Pamuk’s book Snow (Kar) which was set in Kars and when I was there it made total sense that Pamuk would set that strange novel in this very strange place.

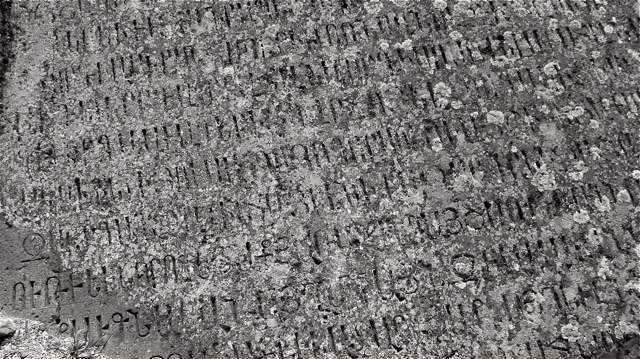

Armenian, Selçuk, Georgian, Mongol, Ottoman, Russian, Turkish; Kars has had the chequered history of a city that is located at the confluence of empires. For most of the 20th century the town was the object of territorial tussles between the Russian and Ottoman Empires, frequently switching hands. In her article on biodiversity in Kars, Elif Batuman writes that when the Russian poet Pushkin decided to travel outside the realms of the Russian Empire he came to Kars. However, by the time he reached Kars it had been taken by the Russians and so Pushkin realised he was still in Russia after all. Kars spent its longest spell as a Russian town, when after the Russo-Turkish War (1877 – 1878), it was transferred to Russia under the Treaty of Stan Stefano. The city became part of modern Turkey when Kazim Karabekir’s troops took the city in 1920. Today it is located on the border with Armenia and not very far from Georgia.

Kars has the air of a city that has seen better times. At one time being a border town was advantageous and the city boomed. The Armenian-Turkish border was closed in 1994, when the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict broke out and has not been opened since. As a result, Kars has suffered. Its location, which was once an advantage, has now relegated it to the status of effectively being an outpost.

There is still a certain Russian air that Kars has. I kept hearing people speaking Russian while I was there. There is probably a strong underbelly that keeps trade between the closed borders going. The Russian past is also quietly referenced at almost every turn by the samovars you see. I never saw traditional Turkish çaydanlıks, but rather the very Russian-style samovars at all the tea houses. It was nice to see that they were still being used because in many other ways the other Russian influence – the architecture – is going to shit.

There are still remnants — broken and tired — of Baltic architecture here. The basalt rock houses with their clear lines add to a sense that this town has a history that it does not share with others in Turkey. But the beautiful 20th century Russian buildings have been overtaken by really atrociously bad concrete structures that hurt the eye. Imagine a cowering old basalt house with a multi-storied pink apartment block on one side and another multi-storied yellow apartment block on the other. TOKİ, the organisation that is in charge of housing development projects in Turkey had signs all over the city. It didn’t make me hopeful. If anything, Kars will probably see an explosion of ugly, cheap construction projects. Unfortunately, that will only make it more similar to other cities in this country, and less like Kars.